The Challenges of Auditing Local Redistricting

In early 2021, the U.S. Census Bureau will begin reporting the results of this decade’s nationwide count of population. Thanks to the Constitution and some landmark Supreme Court cases decided in the 1960s, every level of elected government with districts in the nation will be required to look at these new figures and redraw their lines to balance out populations if necessary.

In many states, this will be a fight. The fate of the U.S. House and each state legislature for the coming decade will be determined in part by which voters get drawn into which district, and both parties have a strong interest in making those choices friendly for themselves. There will be gerrymanders, there will be lawsuits challenging the gerrymanders, and millions of dollars will be spent by both parties to grind out an advantage.

City and county governments must also go through the process. Some of these will be just as dramatic as their federal and state cousins, but for the average local government, redistricting will be low stakes and have few — if any — observers checking on what sort of outcomes their councils and commissions are producing.

Some of the lack of observation is due to a lack of interest. However, if a researcher wanted to do a broad study of local redistricting, they’d quickly find that the data collection is a major task. Jesse Clark wrote on this blog about the challenges of collecting precinct boundaries for pairing with election results, and in many ways, the challenges with local district data are similar. In some ways, though, it is more difficult: the Census Bureau collects and releases congressional, state legislative, and precinct geography — caveats aside about the exceptions Clark raises — but it has no similar program for city and county commission districts.

And while being able to pair precinct election returns with their geography is important in many different avenues, including things like Voting Rights Act enforcement, there are basic representational factors at play when talking about the districts of an elected body. For example, the same constitutional requirement for equal population that states need to follow applies to districts for a county commission, and if violations exist, it would be worth knowing about them.

The collection process

With no national collection effort of these boundaries, we must turn to the states, or more often, the localities themselves. The ideal is to have Census-like digital data, ready for use in mapping software for analysis and comparison with demographic data, but this is not always the case. In my experience with a research project looking at county commissions and my work with the VEST team [link: https://twitter.com/vest_team], I’ve been able to divide the collection experience into five different categories, ranked from friendliest to least friendly.

Level 1: Digital mapping data available online.

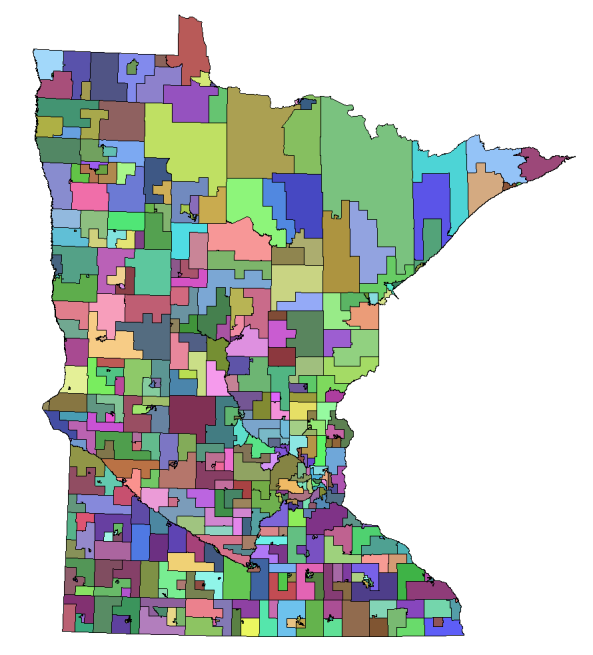

This is the best-case scenario and matches (or exceeds) the U.S. Census in availability. There are some states as a whole that meet this standard, collecting this information from their counties and providing it in a centralized location. Minnesota and Oklahoma are examples.

Level 2: Digital mapping data available by request.

Often, a county will make available its commission districts via a PDF or through a Google Maps-style interactive map, but not provide the underlying data used to create them. It is rare for a county to be unable or unwilling to provide one upon request, though, so this is only below level 1 in taking an extra couple of steps.

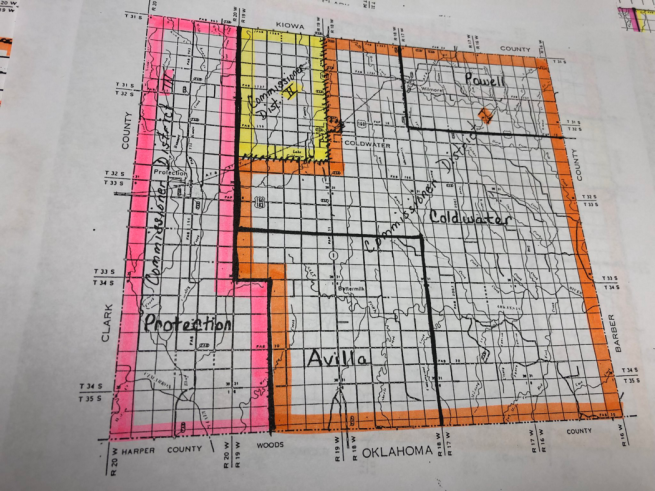

Level 3: High-quality print map or district descriptions available.

In some cases, a PDF or print map will be all the county is able to provide. In small counties, it is not uncommon for this to happen due to the actual districting being done by hand rather than on a computer. Another possibility is that a consulting firm or state agency handled redistricting and did not pass on the base data files. Regardless, if the lines are relatively simple, clearly follow existing boundaries, and/or are of high enough resolution, the maps can be recreated from these sources.

Level 4: Low-quality print map or district descriptions available.

Not only does the map need to be recreated, but communication with the county about ambiguous boundaries also needs to be made during the process. A good approach is to send a high-resolution copy of the final prepared map back to the county to check for errors.

Level 5: No map available.

Presumably a map does exist somewhere, but county officials are unwilling to share. More commonly, they are willing to share, but (often needlessly) require someone to make a copy of the map in person. Counties that charge for maps may also be placed in this level.

Early findings

A basic question we can ask about city and county district maps is whether they look like state and congressional district maps. If so, the effort required to collect and digitize the Level 3–5 localities may not be worth it. However, we already know the drawing process is different in many ways in these counties compared to a state drawing process, so there is good reason to expect that the output is different.

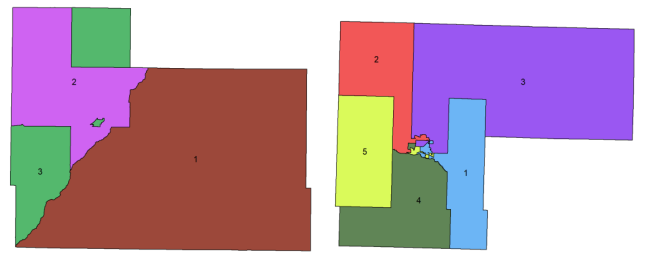

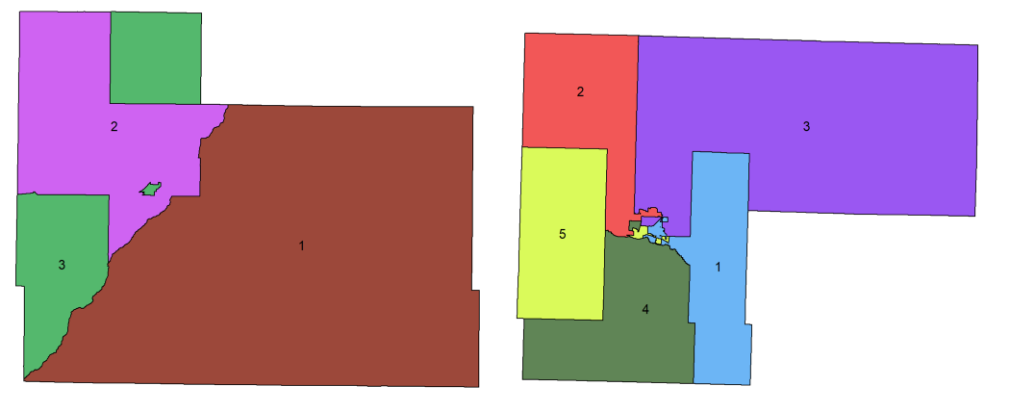

And in the early work I’ve done on county commissions, it looks like the answer is no, the maps do not always look like state and congressional maps. For example, districts that are non-contiguous — meaning that they are made up of two or more pieces of land separated by other districts — are incredibly rare at the higher level. In Kansas’s counties, however, they are relatively common.

Left: Edwards County, Kansas’s commission districts. Right: Finney County, Kansas’s commission districts.

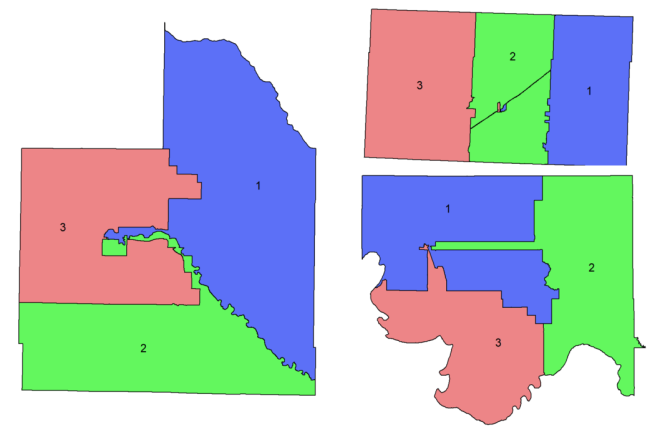

In Oklahoma, where the state collects maps from all counties, there is a significant bias towards splitting up county seats across multiple districts, even when controlling for population. Some of the ways this is accomplished are visually bizarre.

Left: Woodward County, Oklahoma’s commission districts. Top right: Texas County, Oklahoma’s commission districts. Bottom right: Jefferson County, Oklahoma’s commission districts.

More troubling, though, is that some counties fail on basic constitutional requirements. Like the legislatures that were the catalyst for the 1960s Supreme Court cases that mandated equal population across districts, it appears that decennial redistricting is not always carried out, and this can lead to imbalance over time. For instance, Floyd County, Indiana has a district with a population of 49,252, and another with a population of just 11,131.

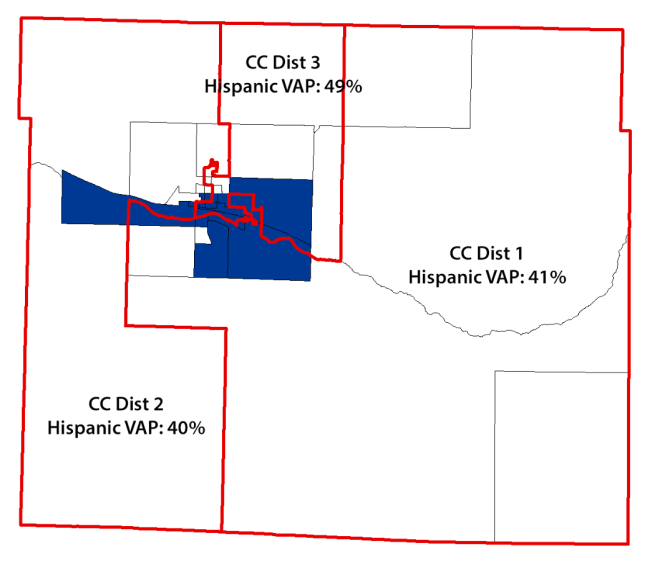

This also applies to Voting Rights Act protections for racial and ethnic minorities. While an evaluation of a violation of Section 2 of the VRA requires a more detailed analysis, a look at Ford County, Kansas raises suspicions. District lines cut through the middle of the densest Hispanic region of the county, and as a result, the Hispanic voting-age population stays under 50% in each of the three districts.

Ford County, Kansas. Red lines: county commission districts. Black lines: census block group lines. Blue polygons: majority Hispanic VAP block groups.

Recommendations

Like I recommended with Michael McDonald in a previous post about catching district assignment mistakes on voter registration lists, better collection of the district boundaries is an obvious first step to fixing potential problems. Allowing outside observers to easily audit these plans would be a valuable check to make sure constitutional rights are not being infringed.

States should go a step further, though, and prevent these mistakes from occurring in the first place. Minnesota not only collects and posts all its county commission districts, but in the last round of redistricting, the Secretary of State’s office also invested resources into guiding localities in the process and set deadlines for action. As a result, they all appear to comply with basic neutral redistricting criteria. States should be thinking now about putting into place similar programs so that they are prepared next year.