MEDSL Explains: Voter Turnout

It’s a way to gauge the health of our democracy — but how do we measure it?

Gauging the health of the electoral process in the United States is an important piece of the work to maintain our democracy overall. One way to do so is to use voter turnout, a seemingly straightforward measure of civic participation that many people believe is the best gauge of the health of our electoral process. Measuring turnout, though, can be more difficult than it first appears. And the complications in measuring turnout also mean that understanding how and why it changes from year to year can also be difficult.

Zooming out to look at the issue from 10,000 feet, it’s clear that important legislation passed in the twentieth century — most notably the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — has led to a long-term increase in the ability of Americans to participate in elections. Other legislation that was intended to increase voter turnout (like the National Voter Registration Act,) have had more limited effects on how many people actually vote in any election year.

Beyond a simple way to measure how healthy our electoral process is, voter turnout also attracts attention (especially in election years) as a way to change the predicted results of an election. Generally speaking, Americans who vote tend to have different demographic characteristics than those who don’t. Given that information alone, it might be reasonable to expect that an increase in turnout (and therefore an increase in voters from other demographic groups,) would have a significant impact on the chance that a different candidate might win. But research indicates that actually, the political attitudes of non-voters are not much different than those of voters. So, even successful efforts to “get out the vote” and expand the electorate may have less impact on overall election results than many people expect.

What is ‘voter turnout’?

Because high voter turnout is considered a mark of a thriving democracy, policymakers and citizens often support electoral reform measures based on whether they will increase turnout, either overall or for particular groups.

The idea of voter turnout is simple: we should know how many people voted. Measuring it, though, is complicated. And even if we have an accurate count of the number of people who voted in an election, it’s often unclear what turnout should be compared to in order to see if it is “high” or “low.” The number of eligible voters? Registered voters?

Political debates often rage over whether particular reforms will raise or lower turnout for particular groups or for the electorate overall. Despite the political heat these debates generate, academic research suggests that in most cases, policy change itself usually has little or no effect on voter turnout.

If the idea of exercising your civic rights & responsibilities doesn’t excite you, the awesome sticker & accompanying bragging rights definitely should.

Measuring Turnout

Data from the United States Elections Project (USEP) indicate that 138.6 million voters participated in the 2016 presidential election. How do we reach that number?

Turnout can be measured in the aggregate by simply counting up the number of people who vote in an election. Not every state does this, however. In 2016, four states (Mississippi, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Texas) did not record how many people turned out to vote. The closest we can come in these states is to count the number of people who cast a ballot for a candidate, usually the one “at the top of the ticket.” This almost gives us the full number, although it leaves out the 1%-3% of voters in an election who choose not to cast a vote for the highest office on the ticket.

Once we’ve settled on how to measure the number of people who voted, we need to compare it to the size of the eligible voting population, by calculating the turnout rate. The easiest comparison we can make is with the voting age population (VAP) — that is, the number of people who are 18 and older, who would theoretically be able to register and vote. (This number can be calculated according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.) But this solution leaves out some critical complications: the VAP includes individuals who are ineligible to vote for many reasons, such as non-citizens and folks who have been disenfranchised because of felony convictions. So, two additional measures of the voting-eligible population have been developed:

- Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) , which is based on Census Bureau generated using the American Community Survey.

- Voting Eligible Population (VEP), which is calculated by removing felons (where they are disenfranchised according to state law), non-citizens, and those judged mentally incapacitated.

Which measure you choose for the denominator in your calculation of the turnout rate depends on the purpose of your analysis and the availability of data. Usually, VEP is the most preferred denominator, followed by CVAP, and then the VAP.

The estimated VEP in 2016 was 230.6 million, compared to an estimated VAP of 250.1 million.

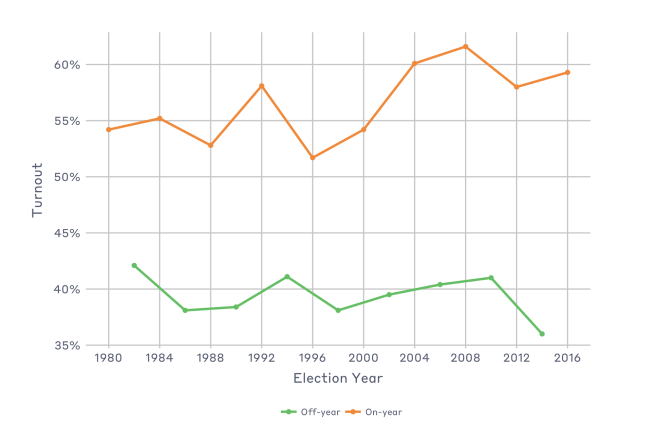

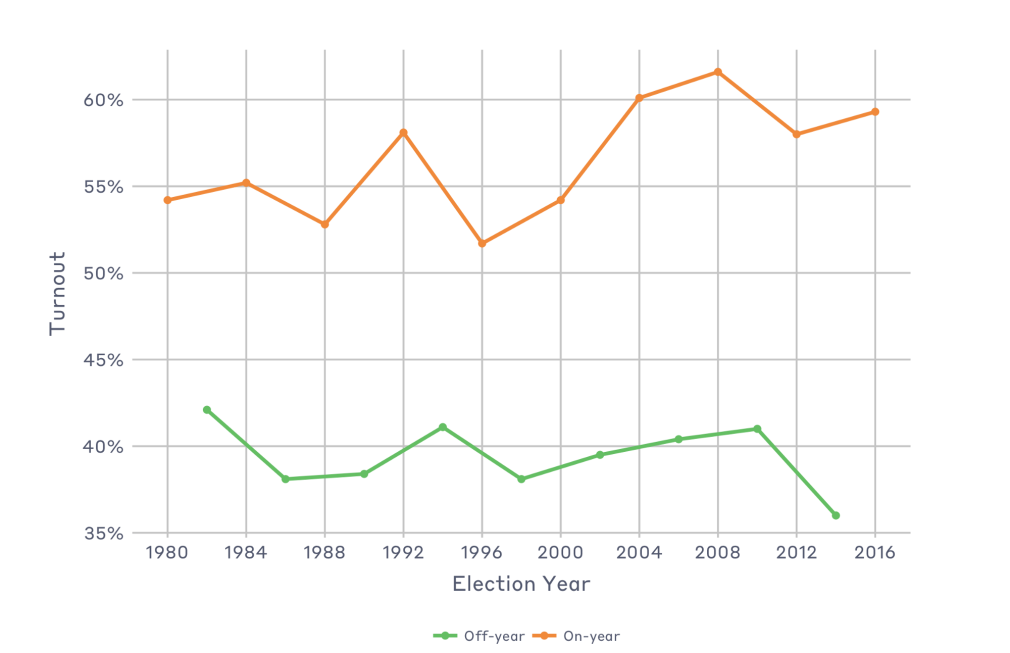

The graph below shows the nationwide voter turnout rate in federal elections (calculated as a percentage of VEP by the USEP,) from 1980 to 2016. In addition to the variation across time, the most notable pattern in this graph is the difference in turnout between years with presidential elections (“on years”) and those without presidential elections (“off years”). Elections that occur in odd-numbered years and at times other than November typically have significantly lower turnout rates than the ones shown on the graph.

Note: Original data were downloaded from The United States Election Project.

Note: Original data were downloaded from The United States Election Project.

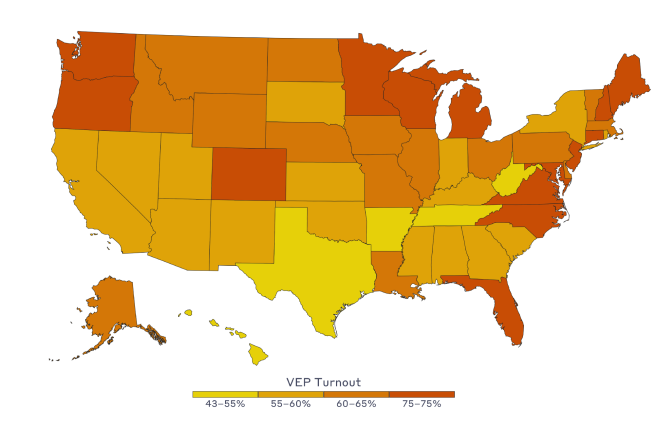

Setting aside the national-level data, we can also see turnout rates for each state — for example, the map below shows the state-by-state turnout rates from the 2016 election. Although there are exceptions, states with the highest turnout rates in presidential elections tend to be in the north, while states with lower turnout rates tend to be in the south:

Note: Original data were downloaded from The United States Elections Project.

Note: Original data were downloaded from The United States Elections Project.

Studying voter turnout

Sometimes we want to measure the turnout rates of particular groups of voters, or study the different factors that lead individual citizens to vote. In these cases we need individual measures of turnout based on answers to public opinion surveys.

The chief difficulty in using public opinion surveys to measure individual voter turnout is the problem of social-desirability bias: that is, many respondents who did not vote will say that they did in order to look like good citizens. As a result, estimates of turnout rates based on surveys are higher than those based on administrative records. For example: 78% of respondents to the 2012 American National Election Studies survey reported voting, compared to the actual turnout rate of 58%.

To guard against over-reporting turnout in surveys, a few studies use voter registration records to independently verify whether respondents voted, but not many. (Of course, if we knew that all groups over-reported whether they voted by equal amounts, it would be safe for us to use these surveys with less caution — but there is evidence they don’t.)

Even with the problems of over-reporting, though, public opinion surveys are usually the only way we can study the turnout patterns of certain segments of voters, such as regional or racial groups.

One survey often used to compare turnout rates for different groups is the Current Population Survey (CPS) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. In the Voter Registration Supplement , which is administered every November in even-numbered years, respondents are asked whether they voted in the most recent election. Because the CPS already has a rich set of demographic information about each voter and has been conducted for decades, this is often the best source of data for looking at smaller groups of voters.

The dominant theory for why voter turnout varies from year to year focuses on a type of cost-benefit calculation, as seen from the perspective of the voter. According to this theory, voters weigh what they stand to gain if one candidate beats another against the economic or social costs that voting poses for them. Conversely, other scholarship has challenged this approach by showing that going to the polls is largely based on voting being seen as intrinsically rewarding.

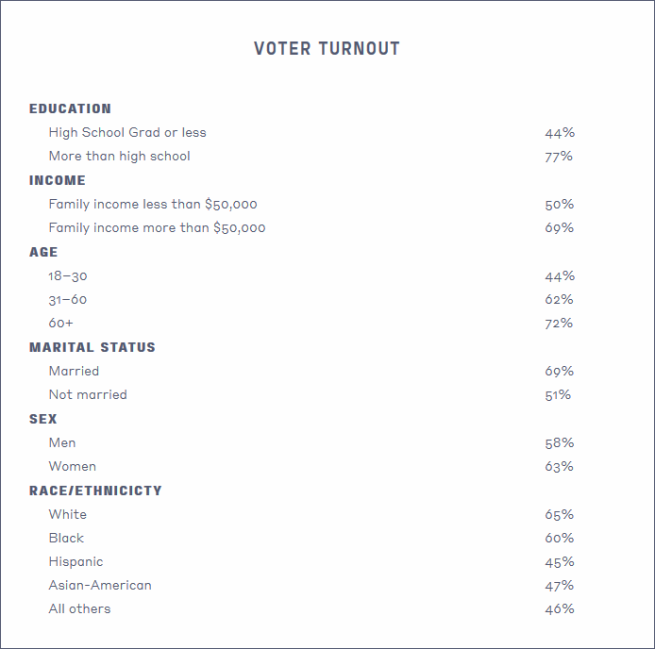

A long history of political science research has shown that the following demographic factors are associated with higher levels of voter turnout:

- more education

- higher income

- older age

- being married

In addition, women currently vote at slightly higher levels than men. The chart below lays out a general summary of these factors:

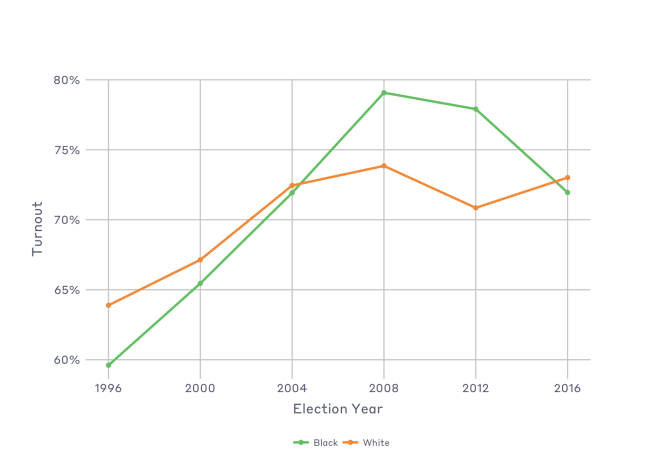

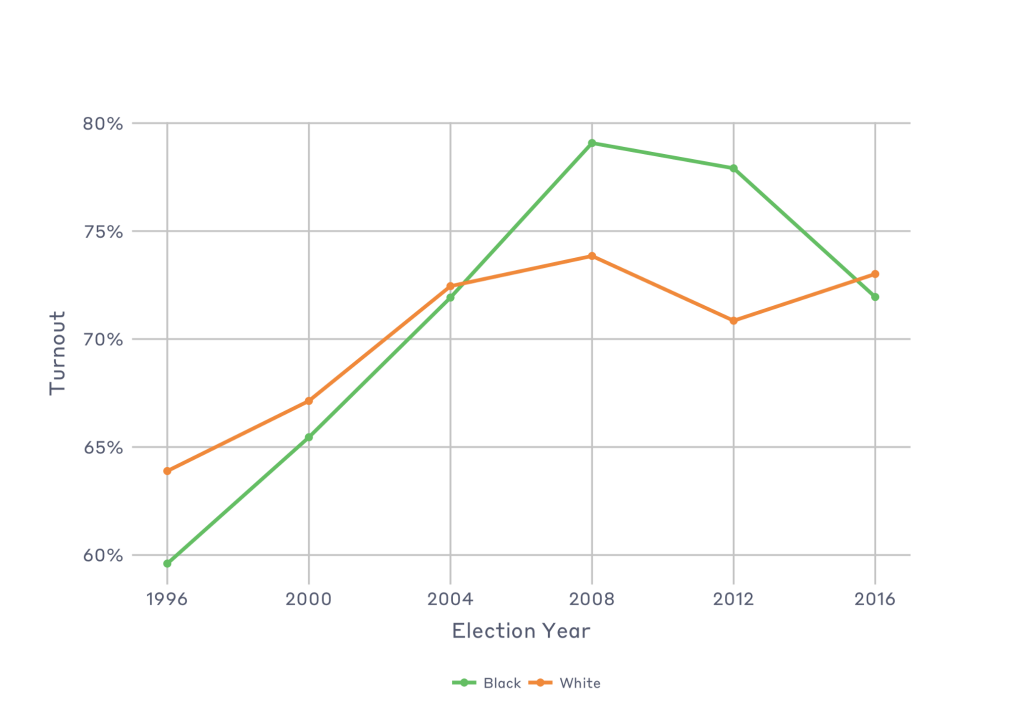

For decades, African-Americans voted at lower levels than whites. As the graph below illustrates, however, blacks and whites have now reached rough parity in recent national elections. Hispanics and Asian-Americans still vote at lower levels than whites and blacks.

Can reforms increase turnout?

Can particular election reforms — Election Day registration, vote-by-mail, early voting, photo ID requirements, etc. — have an effect on voter turnout? Unfortunately for those hoping for an easy answer, research results in most of these areas have been mixed at best. The one reform that is most consistently correlated with higher levels of turnout is Election Day registration (EDR). But even here, there is disagreement over whether EDR causes higher turnout or if states with existing higher turnout levels are more likely to pass EDR laws. (It’s probably a combination of the two.)

What about the roles that campaigns play in stimulating voter turnout? This is most visible in presidential elections, where candidates pour disproportionate resources into campaigning in battleground states, which are closely divided along partisan lines and thus are most likely to swing the result of the Electoral College vote.

In 2016, the average turnout in the 11 states where the presidential margin of victory was 5 percentage points or less was 67%, compared to 56% in the seven states where the margin of victory was greater than 30 points. (For the states in the middle, the average turnout rate was 61%.)

Field experiments to test the effects of campaign communications on voter turnout have shown that personalized methods work best in mobilizing voters. Mass e-mails are virtually never effective in stimulating turnout.

What if everyone voted?

We care about turnout levels for two reasons:

- They’re considered a measure of the health of a democracy, so higher turnout is always better than lower turnout.

- If we believe that lower turnout levels exclude citizens with particular political views, then increasing turnout would “unskew” the electorate.

Early research seemed to justify skepticism that increasing turnout in federal elections would radically change the mix of opinions among those who actually vote. More recent research, however, suggests that although voters in national elections are more likely to be Republican and to oppose redistributive social policies than non-voters, the differences between voters and non-voters on other issues (such as foreign policy,) are much less pronounced.

When it comes to local elections, overall turnout rates tend to be much lower in elections held during off-seasons (essentially, any month except November, and any day that is not also the day of a presidential or midterm election), than elections that are scheduled to coincide with federal elections. On top of that, the demographic characteristics of voters in these elections are much more skewed compared to non-voters.

It’s fair to say, without partisan bias, that keeping democracy fighting fit means continuing to investigate ways to support higher voter turnout. We look forward to new research exploring the factors that affect turnout, and to the continuing conversation on how that research can help the work of election officials and those working to help citizens vote.