The Role of Law Enforcement in Elections

As if navigating the challenges of COVID-19 and new election-focused legislation wasn’t daunting enough, election officials are also facing increased threats.

As state and local election administrators gear up for the midterm elections this November, the 2020 election is likely not far from their thoughts.

Content note: This piece includes strong language and explicit mentions of violence

Introduction

The last election cycle presented myriad challenges for those working in elections, forcing them to pivot their practices quickly to keep voters (and poll workers) safe and enfranchised. Against their admirable efforts, the election in 2020 featured an unprecedented surge of institutional roadblocks, exacerbated by the global pandemic: as the Brennan Center documents, millions of voters navigated newly-imposed strict voter I.D. laws; high-profile attacks on mail voting spread distrust and misinformation about election security; and many locales saw a decrease in their polling places and ballot dropboxes, among other changes. Since then, election scholars and practitioners alike have been studying the events of the 2020 election cycle under a microscope: figuring out what went wrong, what went right, and brainstorming solutions to the challenges presented by a shifting election landscape.

As if navigating the challenges of COVID-19 and new election-focused legislation wasn’t daunting enough, those in the field are also facing increased threats against election officials. Most of these violent messages echo sentiments of the “Big Lie:” the false claim promoted by Donald Trump and his supporters that the 2020 election was somehow fraudulent. This bogus conspiracy theory spread like wildfire in far-right circles after Election Day, and quickly began to impact American democratic institutions. As a report by Reuters demonstrates, election officials at every level, from rural local poll workers to high-profile Secretaries of State, have received threatening phone and email messages from supporters of the Big Lie vowing to harm them and their families if they fail to declare or certify election results in a certain way (regardless of the actual vote counts) or “crack down” on nonexistent fraud.

The increase of these threats in the last few years has prompted election administrators to take action in order to keep themselves and their workers safe. One of the most common strategies to address similar concerns in the past has been to increase the presence of local law enforcement at polling locations and surrounding areas. While this strategy is meant to ensure election workers’ safety, evidence suggests that increased police presence in the election space does not significantly reduce threats of violence. This piece will investigate the extent to which this is true and explore why difficulties persist for law enforcement attempting harm-reduction.

It is worth noting this issue is more complex than one short article can address. One important factor to consider in looking at police presence at polling places is the historically strained relationship between law enforcement and marginalized communities, particularly African-Americans. Therefore, this piece will also call attention to the dimensions of this issue that have not been widely explored in the greater literature, including how voting behavior and attitudes are impacted by police presence at polling locations, and the role of intimidation in some citizens’ encounters with law enforcement. While these topics may seem only tangentially related to the issue of threats against election workers, they are in fact all crucial pieces of a larger puzzle: bolstering the integrity of our democracy by ensuring that all voters and election officials feel safe and able to participate in the democratic process.

Rising Threats Against Election Officials: An Overview of the Problem

Most election administrators feel unsafe, in some cases to such a high degree that they no longer feel able to do their jobs. According to a survey of election workers conducted by the Brennan Center for Justice in March 2022, one in four election administrators fear being threatened on the job, while one in six reported actually experiencing attacks.

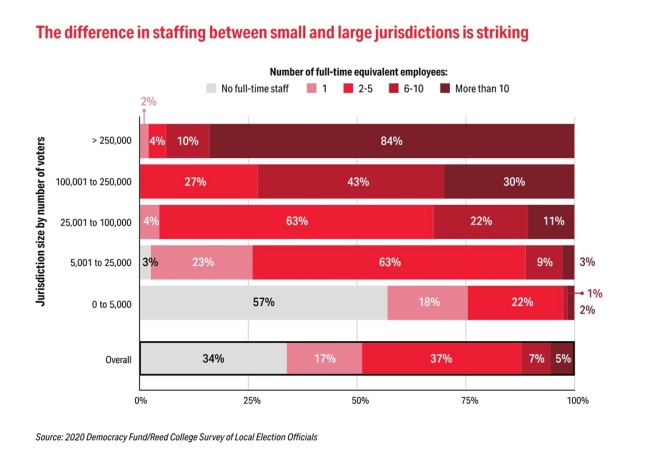

This widespread sense of fear has prompted many election workers to resign or retire early: 20% of workers surveyed plan to leave before the 2024 election, and many fear that they will be replaced by partisan zealots hoping to ensure their candidate wins. Not only would this violate a core principle of democratic institutions, the staffing shortage would lead to significant slow-downs to the election administration process, including long lines at polling places and delayed election results. The negative effects of understaffing elections are serious, and they are projected to worsen if action isn’t taken to adequately protect officials against threats. A survey conducted by Reed College and Democracy Fund in 2020 found that small, local election jurisdictions have been hit the hardest (as they often are) by the worker shortage, for these officials are paid less and work longer hours than their state-level counterparts, on average.

Source: 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Election Officials.

The physical and verbal threats against election officials are largely generated from supporters of the Big Lie who claim “corrupt” election administrators intentionally miscounted the ballots in the 2020 presidential race and falsely led Joe Biden to victory over Donald Trump. The majority of threats and violent messages occur over the phone; one jarring example is the call made to Staci McElya and other workers in the Nevada Secretary of State’s Office: “I hope you all go to jail for treason…You’re all going to f—ing die.”

A significant number of threats are delivered via social media, often by direct-messaging election workers or commenting on posts made on their accounts. Colorado Secretary of State Jenna Griswold, for example, received a Facebook message that read, “Watch your back. I KNOW WHERE YOU SLEEP, I SEE YOU SLEEPING. BE AFRAID.” Just days earlier, Griswold’s office answered a telephone call where the caller claimed he was “going to shoot every employee in the building.”

In sum, the Big Lie has been the driving force behind the threats against election workers, making them fearful and prompting them to resign. This has had severe administrative consequences, prompting election workers to enlist the assistance of law enforcement to combat threats of violence. But is this strategy effective?

The Effectiveness of Police in Election Administration

Though many people associate increased police presence with greater security, local law enforcement have largely been unable to diminish the number and severity of threats made against election officials. This is for several reasons: for one, it is often unclear what police can and cannot enforce when it comes to election-related harassment and violence, especially if the threats are occuring in the digital space where people can easily remain anonymous. Perpetrators may be from outside the state, which makes prosecution difficult even if their identities were known. Additionally, threats made against election officials are unlikely to withstand trial because of the True Threat Doctrine, a law stating that there must be clear “intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death” in order to criminally charge someone for physical or verbal threats. In a statement given to the New York Times, Catherine J. Ross, a professor and expert on First Amendment law at George Washington University, said,

“You need to say something like, ‘I am going to kill you.’ It can’t be ‘Someone ought to kill you.” That’s a very high bar, and intentionally a high bar.”

Reuters, one of the leading news agencies that has been documenting threats against election officials, reported that out of over 100 threats nation-wide, there have been only four arrests and zero convictions (as of September 2021). Victimized election officials have reported that law enforcement officers have not taken their reports seriously or claimed no authority to investigate and directed them to the FBI. Furthermore, despite the Justice Department creating an Elections Threats Task Force designed to address reported violence, 90% of election officials surveyed by the Brennan Center for Justice reported that they were unaware of the task force’s existence. These statistics highlight the ineffectiveness of law enforcement to prosecute and prevent hate crimes committed against election officials.

Opportunities for Further Analysis

In addition to the role of law enforcement in preventing threats against election officials, there is much more to be explored on the topic of law enforcement in the election space. For example, investigating the effects of police presence at polling locations could provide valuable insight into the behaviors and attitudes of voters, particularly across racial groups. Given the complex historical relationship between racial minorities and law enforcement, it is plausible that police presence at polling places could have an effect on the turnout of voters of color, as well as their attitudes about the voting process. Indeed, a study conducted in 2021 by Dr. David Niven at the University of Cincinnati investigated this question, and determined that police presence at polling locations in Alabama was associated with a 32% reduction in African-American voter participation.

An expansion of this research would involve investigating the effects of police presence at polling places in various locations across the country, perhaps adding the dimension of time to observe how voter turnout and police presence change with the Trump presidency and the rise of the Big Lie. It would also be valuable to conduct qualitative data (such as with a survey) in order to get a holistic understanding of the attitudes voters of different races have as it relates to authority, safety, and election security. Does the presence of law enforcement lead some voters to place greater trust in the voting process? Are voters of color more likely to feel intimidated by the presence of police and thus prefer to vote absentee? Future studies that address questions like these would be an asset to scholars, election administrators, public officials, and others invested into ensuring the safety and integrity of American democracy.

Conclusion

The rise of threats against election officials since 2020 is a much more complex problem than meets the eye. It is evident that the Big Lie is the driving force behind this violence, and such conspiratorial thinking will continue to jeopardize democracy if left unchecked. While existing literature provides valuable insight into the role of law enforcement in the election space, there are many dimensions to this topic that have yet to be fully understood. Investing in research that explores how police presence may influence voter turnout, attitudes about election security, and more is essential for keeping elections free, fair, and safe. Protecting the integrity of democracy is neither a simple nor straightforward task, but understanding the place of law enforcement in elections is essential for developing effective solutions.